Knowledge of the World

Sunday, April 23, 2006

Language is arguably one of the main mediums used to transmit ideas and knowledge. With this premise in mind, as of late, I have been toying with the theory that if knowledge is transmitted via language then a large portion of the world's knowledge to date is lost on the edges of some average distribution of a language/knowledge continuum.

According to ethnologue.com, there are 6,912 known spoken languages in the world. Within all these languages, there is common knowledge that has been transmitted over the centuries either through spoken stories or written works. However, not all of it makes it to every remote spot of the world.

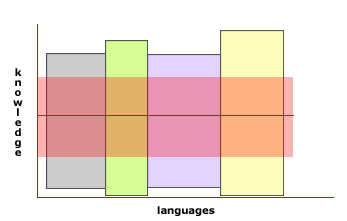

I argue that we have a common knowledge base throughout the world, which I represent as follows:

- The vertical axis represents the knowledge accumulated from every language; the red band represents the common knowledge we share as a global culture.

- The horizontal axis represents the languages spoken (I have no space for 6,000 bars, so 4 bars will have to do)--there is no particular order the languages are presented.

- As per the width and height of the bars, you can think of each language being more expressive or contains a larger amount of words or phonetic sounds when compared to other languages (think of Chinese or Russian).

Hence, putting all the languages of the world side by side and conceptually estimating the knowledge accumulated globally, I end up with bits of information that, I claim, lie outside the red band, and these bits are knowledge that has been lost in translation.

This being a thought experiment, I only have empirical results to support this observation. In particular, I have noted (and probably so have you) that some of the knowledge that does not translate from language to language is actually cultural knowledge. Thus, I present three trivial examples:

- Children's Stories

Latin American folk stories used to scare little children do not exist in North America, and conversely, the boogey man is not part of the vernacular knowledge of Latin American mothers--although moms always find a way to scare us of something (as a defense mechanism, we can now explain).

- Tropical Fruits

How many of you know where cashews come from?

Gabriel thinks they come from cans bought at the super market, or a cashew tree. However, a cashew is actually the seed of a tropical fruit called marañon.

This bit of information does not come from any special training from my part. I actually had a tree in my backyard (in El Salvador, not Canada) and after school my friends and I would pick the ripe marañones, eat the fruit, and then roast the seed (which grows outside of the fruity part) to eat it as an afternoon snack. They were, and still are, delicious.

- Translated Literature

As a global culture, we have found a way to translate literary works without loosing too much of the idiosyncrasies that create the charm of a particular work of art.

For example, I have read Cervantes's Don Quijote de la Mancha in English and Spanish, and have, from time to time, compared paragraphs of certain passages of both versions. It is not surprising to find the concepts of the two version being the same in my mind, even if the physical representation of the words on the pages is totally different (different phonetics, different sentence structure, et al).

This duality of languages and the representation of the same concept in the mind is actually hard to explain, and probably understand, if you do not speak more than one language: things are the same, yet different.

But in this particular example of Don Quijote, both translations of the same work have a common element to it, which is what is translatable and has become the average knowledge that is transferred from culture to culture. (Although master pieces as these translations are, I am certain some aspects of the novel our one handed Cervantes considered important did not quite make it into every translated Don Quijote book.)

Although I call my thought experiment a theory, it hardly qualifies as hypothesis of a problem, as every new theory tries to add new knowledge to our understanding of the world around us. Unfortunately, my "theory" does not really prove anything new. We all know that we should welcome cultural differences and channel them in a way that allows us to learn new things from each culture we encounter. In essence, I am saying that having two different points of view at the same time about a particular issue is actually beneficial--some of that cultural knowledge may be the key to solving intractable problems.

Even though, I have not done any academic research, I can site one research result to back some of my writings (this may be pushing it, but if you squint really hard you can almost see some relationship): Ellen Bialystok, a researcher from York University, has done a more scholastic study relating to

bilingualism and problem solving. For example, CTV reported on her last study:

York University psychologist Ellen Bialystok undertook the study to see if people who speak more than one language react faster in a series of computer tests than people who speak only one language.

According to her results, knowing two languages allowed some of her subjects solve a certain type of problem faster.

Her study seems to be related to what I am trying to present here (which I only found out after writing my entry), although, a more rigorous study or her experiment and her statistical analysis is necessary to be more certain of the results.

I will, however, go further and state the claim that

knowing more than one language allows individuals to have knowledge about different cultures and that this cultural knowledge adds different perspectives to problem solving allowing for a larger spectrum of possible solutions to draw from--noting of course, that a certain aptitude on the field of study is required, i.e., being fluent in English and Spanish does not give me the tools to be any good at brain surgery.

It is a big claim with no backing of anything, except a vague relationship to some obscure study done by one researcher and my three examples together with my fancy (and original) knowledge-language continuum graph. So, I will live it up to you to draw your own conclusion about the connection and claim I made.

What do you think? O mejor dicho, que opinas? :)

Comments:

hola, i found your page by trying to find the meaning to my last name and insted i found i GREAT thought, i agree because when i translate fro spanish to inglish i find myself loosing culture and words. were did your family come from. my grandparents came from sonora, mexico? send me an email @ pinkboxglove@yahoo.com

sorry about the spelling it's late and i did not spell ck

bye !!!!!!